Fusion Technology That Will Lead 2026 Development

From 2025, we have seen fusion development rapidly shift from laboratory science into an industrial reality. It was not just another year of incremental progress; 2025 marked the definitive transition to a commercial landscape. With record-breaking confinement times, historic private investment and multiple technological pathways advancing in parallel, the sector is entering a "deployment phase." While the goal remains carbon-free energy, the "battle" between confinement methods will determine which technology dominates the commercial reality of the 2030s.

Here are the key technological paths shaping the future of fusion energy—and what to watch in 2026.

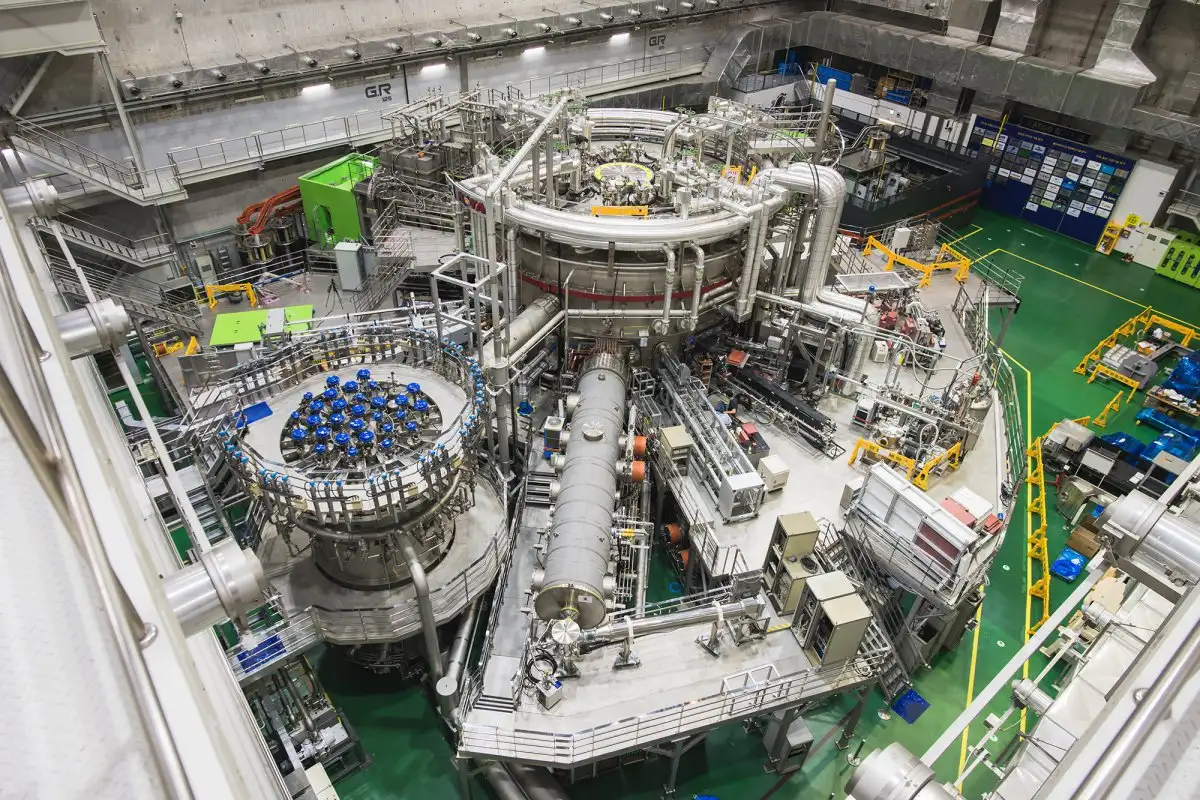

Picture: The Korea Superconducting Tokamak Advanced Research experiment from Korea Institute of Fusion Energy

1. Tokamak

Tokamaks remain the most mature fusion architecture, supported by decades of national programs and the international ITER project. Over the last decade, development steadily shifted from physics validation toward full power-plant engineering. The most transformative breakthrough between 2015 and 2025 was the mastery of high-temperature superconducting magnets, which allow much stronger magnetic fields to be generated in significantly smaller devices. This has enabled compact tokamaks to reach plasma conditions previously achievable only in massive reactors like ITER, drastically reducing plant size, construction time, and projected costs.

In 2025, this technological transition became visible at an industrial scale. France’s WEST tokamak sustained plasma for over twenty minutes, while China’s EAST reactor maintained high-confinement plasma for nearly eighteen minutes, demonstrating the levels of stability and heat handling required for commercial operation. At the same time, ITER completed assembly of its full central solenoid magnet system — the most powerful superconducting magnet ever built — while Commonwealth Fusion Systems secured one of the largest private funding rounds in fusion history and signed a long-term power offtake agreement with Google. These developments confirmed that tokamaks are now approaching the operational endurance and economic viability required for grid deployment.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems, Tokamak Energy, and Gauss Fusion now represent the leading private developers pursuing compact, high-field tokamak architectures. Entering 2026, tokamaks remain the fastest pathway to first grid injection, although long-term operational complexity and maintenance economics remain central engineering challenges.

2. Stellarator

While tokamaks operate in pulses, stellarators are designed for inherently steady-state operation, eliminating the risk of plasma disruptions and enabling continuous power production. Historically, stellarators were limited by extreme design complexity, but advances in AI-driven magnetic optimization and modern superconducting manufacturing have transformed their feasibility.

In 2025, the stellarator concept reached a new level of credibility. Germany’s Wendelstein 7-X facility achieved record energy turnover and sustained high-performance plasma operation, demonstrating that stellarators can maintain the long-duration stability required for power-plant operation. At the commercial level, Proxima Fusion unveiled its Stellaris power-plant architecture and raised Europe’s largest private fusion funding round, while Type One Energy licensed high-temperature superconducting magnet technology and Thea Energy presented its Helios stellarator power-plant design. National fusion programs in Europe, the United States, and Japan have also begun formally assessing stellarators as candidates for grid-scale deployment.

These developments have repositioned stellarators as the leading architecture for continuous baseload fusion generation. Proxima Fusion, Type One Energy, Thea Energy, Helical Fusion, and the W7-X consortium now form the core of the emerging stellarator ecosystem. In 2026, the key question will be how rapidly stellarator designs can transition from engineering models to construction-ready plants.

3. Laser / Inertial Confinement

Laser-driven inertial confinement fusion remains central to national high-energy-density physics programs and long-term high-gain fusion concepts. Following the historic ignition achievements at the U.S. National Ignition Facility, 2025 marked a strategic shift toward Laser-Driven Inertial Fusion Energy, with research focusing on repetition rate, efficiency, and power-plant scalability rather than single-shot experimental performance.

Throughout 2025, European and U.S. programs advanced high-repetition-rate diode-pumped laser systems capable of operating at efficiencies approaching those required for industrial power production. Fraunhofer ILT’s research highlighted major progress in laser driver architectures, while the Laser Fusion Application Panel confirmed that laser technology is now moving beyond massive single-shot glass lasers toward commercially scalable platforms. First Light Fusion also introduced its FLARE concept, which separates fuel compression from ignition, while Focused Energy expanded development funding for modular inertial fusion designs.

Although laser fusion remains further from grid deployment than magnetic confinement systems, it continues to offer the promise of extremely high energy gain and may enable future hybrid fusion-fission or specialized high-power energy systems.

4. Magneto-Inertial Fusion (MIF)

Magneto-inertial fusion aims to combine magnetic insulation with rapid compression in order to dramatically reduce reactor size, cost, and complexity. These systems are designed to deliver faster commercialization timelines and modular deployment models compared to conventional fusion plants.

In 2025, Zap Energy demonstrated major improvements in plasma stability and pressure using its sheared-flow stabilized Z-pinch technology, achieving high performance without the need for large external magnet systems. At the same time, Helion Energy advanced its pulsed non-thermal fusion platform and began construction of its first commercial fusion plant designed to supply power to Microsoft data centers. These approaches signal a new class of fusion architectures optimized for modular deployment, industrial microgrids, and remote energy systems.

All fusion pathways share the same objective: delivering carbon-free, high-density, always-on energy. Yet their architectures differ fundamentally in scalability, operational complexity, and commercialization timelines. The coming decade will determine not only when fusion reaches the grid, but which technologies will become the standard infrastructure of the global energy system. 2026 will increasingly be the year where physics breakthroughs give way to engineering execution.