The Fusion Imperative: Why Emerging Economies Must Act by 2030

The global fusion energy narrative has crossed a structural threshold. What was, for decades, a question of scientific plausibility has now become a matter of industrial execution. Since the first verified ignition at the U.S. National Ignition Facility and its subsequent replication, the debate is no longer if fusion works—but who will control the industrial stack that brings it to market.

By January 2026, fusion has entered its Engineering Validation era. Capital is flowing accordingly: cumulative private investment expanded from under USD 2 billion in 2020 to over USD 15.17 billion by late 2025. This is not speculative climate capital; it is industrial capital targeted at magnets, power electronics, and first-of-a-kind (FOAK) pilot plants. For emerging economies, particularly in Southeast Asia, this shift creates a decisive window. Countries that remain passive technology observers risk "Structural Decoupling"—a permanent exclusion from the highest-value layers of the energy system. The risk is not merely missing fusion power plants; it is missing fusion capability.

The Engineering Validation of Strategic Energy Assets

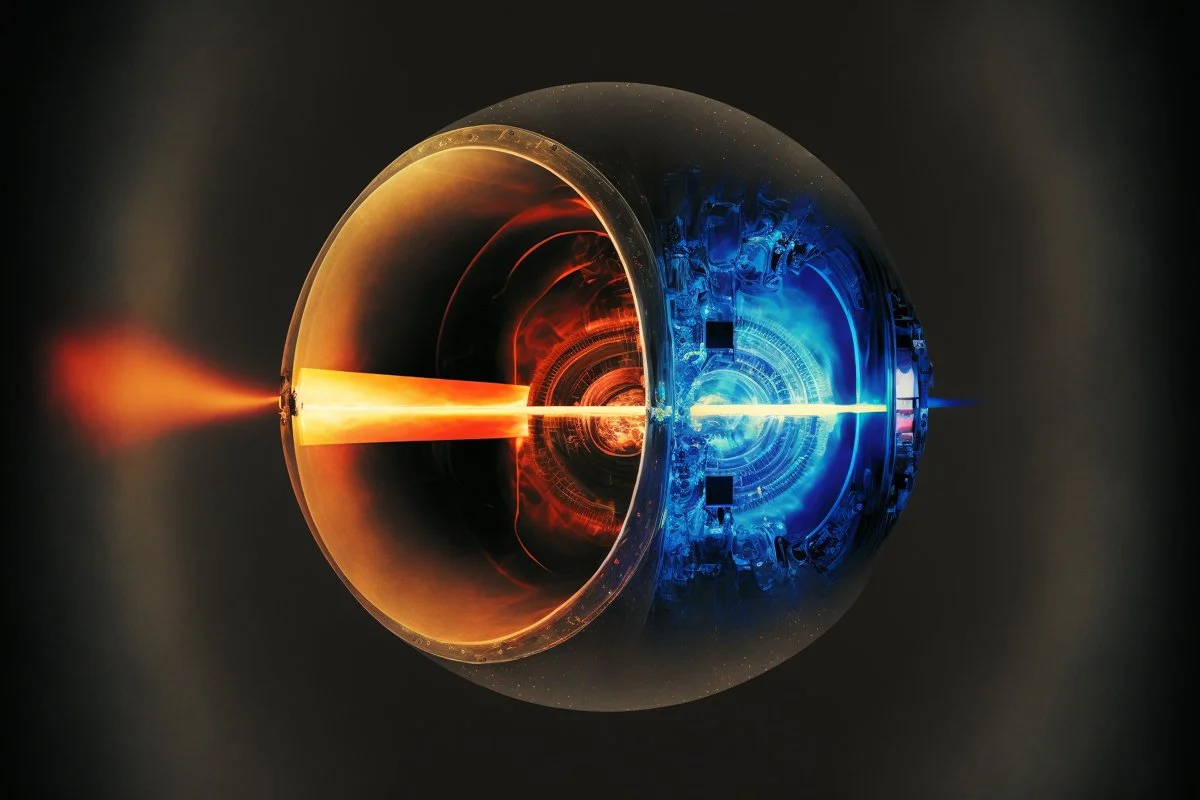

Fusion’s transition mirrors earlier deep-tech revolutions. The critical change is not plasma physics—it is manufacturability. Companies such as Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), Helion Energy, and General Fusion are now judged less on confinement time and more on reliability, maintainability, and cost-down trajectories.

A key enabler is the maturation of High-Temperature Superconductors (HTS). These materials allow magnetic fields significantly stronger than legacy superconductors, enabling reactors that are smaller, modular, and economically addressable by private capital. ITER-scale megaprojects are no longer the sole pathway; fusion has become "buildable". Between 2025 and 2035, the industry focus is FOAK demonstration: proving net facility gain, validating component lifetimes under neutron flux, and integrating systems at industrial scale. Commercial electricity is not the near-term objective—de-risking the supply chain is. For emerging economies, participation during this validation phase determines who captures long-term industrial value.

Fusion as Strategic Baseload in the AI Age

Fusion’s acceleration is being quietly underwritten by an unexpected customer: hyperscale computing.

In emerging regions like Southeast Asia, digital and industrial activity is expected to accelerate through 2026, pushing utilities to prioritize low-emission, high-density infrastructure. A primary motivator for SEA’s urgency is the regional surge in AI data centers, which are projected to double electricity consumption by 2028–2030. Because variable renewables cannot meet the 24/7 constant load requirements of hyperscale AI training, fusion is viewed as the "Gold Standard" baseload required to maintain digital sovereignty in the region.

This reframes fusion’s role in the energy system. It is not a competitor to renewables, but the stabilizing backbone of a post-renewables grid—supporting AI infrastructure, advanced manufacturing, and industrial heat. Countries without access to strategic baseload will find their digital economies constrained, regardless of renewable capacity.

The Southeast Asian Industrial Blueprint

Strategic Participation in the Global Fusion Energy Ecosystem

A critical misconception persists that meaningful participation in fusion requires building and operating power plants immediately. In reality, the highest near-term returns lie in the midstream fusion economy—supplying the components, subsystems, and services every reactor requires.

Emerging economies can leverage existing industrial bases to supply high-value components:

Semiconductors: Power electronics and plasma diagnostics. Malaysia is leveraging its established advanced packaging and testing (APT) semiconductor facilities and rare earth processing (e.g., Lynas expansion) to supply components for high-temperature superconductors (HTS) and fusion-spec vacuum systems.

Mining: Rare earth and tungsten extraction for high-performance materials. The Philippines is exploring the use of its substantial copper reserves for power electronics and magnet manufacturing within the fusion supply chain. Vietnam, as the second-largest tungsten producer outside of China, is a critical hub for supplying the plasma-facing components essential for fusion reactors.

Regional Momentum Highlights:

While individual nations are at different stages of nuclear development, the region as a whole is building the "Industrial DNA" required for fusion readiness.

Thailand’s Hardware Leadership: The Thailand Tokamak-1 (TT-1), which officially began operations in July 2023, made Thailand the first Southeast Asian nation to operate a tokamak. As of 2026, TINT is using TT-1 to build a "Hub of Talents," testing diagnostics and plasma control technologies to bypass "Scientific Latency".

The Philippine-Malaysia Regulatory Asset: The passage of the PhilATOM Law (RA 12305) in late 2025 established an independent nuclear regulator. Similarly, Malaysia updated its Atomic Energy Licensing Act in 2025 to emphasize international safeguards and transparency, positioning it as a stable partner for foreign fusion developers. This institutionalizes Malaysia’s nuclear preparedness, ensuring that any potential adoption of advanced energy is orderly, transparent, and aligned with international standards.

The Vietnam-Indonesia Pivot: Vietnam enacted its Law on Atomic Energy (taking effect Jan 1, 2026) to facilitate projects like the Ninh Thuan plants, which aim for 4,000-6,400 MW by 2035. Similarly, Indonesia targets 500MW of nuclear capacity by 2032, leveraging Sumatra and Kalimantan to host facilities. These frameworks for fission serve as the baseline for future fusion integration.

The Tritium Constraint: Fusion’s most severe bottleneck is fuel. Commercial reactors face an acute tritium scarcity, with global stocks projected to peak at just 27kg in 2027. Without internal breeding using Lithium-6 blankets, large-scale deployment is impossible. This constraint elevates the strategic importance of Lithium-6 processing and isotope management—domains where emerging economies precisely where regions like SEA can play as midstream hubs.

The Post-Renewables Divide

By the mid-2030s, the global energy landscape will be defined by a new divide. On one side: economies reliant solely on variable renewables and storage. On the other: "Strategic Baseload" nations that have successfully integrated fusion energy into their industrial DNA.

The year 2030 is the final deadline for emerging economies to secure their place in this transition. Those that act now—by securing critical mineral chains, pioneering regulatory frameworks, and investing in ecosystem equity—will lead the next century. Ultimately, the successful integration of these regional initiatives into a cohesive strategy will ensure that emerging markets do not just meet their local energy goals but become essential pillars of the global fusion economy.